The return of equatorial Atlantic extreme events

The return of equatorial Atlantic extreme events

(F. P. Tuchen, University of Bremen, Germany & member of the CLIVAR Atlantic Region Panel)

Back in April 2023, it was surmised that, after a relatively quiet time of almost two decades (Prigent et al., 2020), episodes of extreme ocean surface temperatures might once again be emerging in the equatorial Atlantic. Now, a few years on, that hunch has proven correct.

The equatorial Atlantic warm event of late 2019 (Richter et al., 2022) and the strong Atlantic Niño of 2021 (Lee et al., 2023) marked the start of a new phase of more frequent extreme events in this region. In 2024, a record-breaking warm event was recorded, followed by an abrupt transition to unusually cold ocean temperatures (Tuchen et al., 2025). This year, observations indicate the development of an extreme cold event in the equatorial Atlantic during the Northern Hemisphere (boreal) summer.

In this blog, we first revisit the origin of extreme events in the equatorial Atlantic and explain why sustained observations and improved understanding of these extreme events are crucial. We then take a closer look at this year’s cold event and what it might reveal about the changing dynamics of the tropical Atlantic.

______________________________________________________________________________

Normal and anomalous changes of sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Atlantic

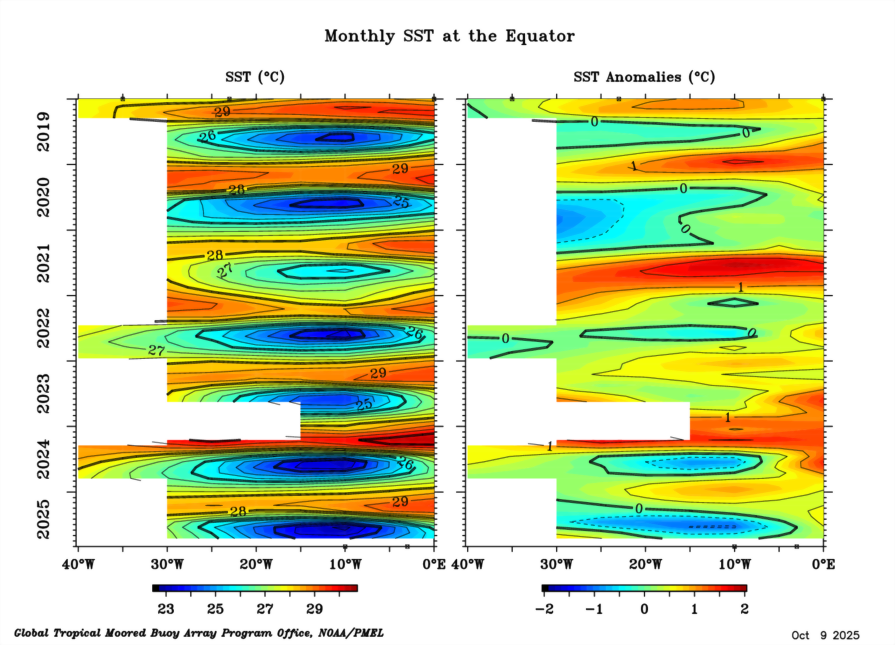

A typical year at the equator follows a familiar pattern. Early in the year, solar radiation is at its peak as the sun passes directly overhead. By June-August, the sun has shifted northward, solar heating weakens, but the winds blow stronger over the eastern equatorial Atlantic (20°W-0°) and the ocean surface cools rapidly due to increased upwelling of colder waters from below. Sea surface temperatures (SST) generally range from about 28-29°C early in the year and drop to around 24-25°C in boreal summer. This seasonal rise and fall is entirely normal and is well known from both satellite observations and measurements from moored surface buoys along the equator (Fig. 1; left panel).

However, the strength of this seasonal cycle may vary from one year to the next. In some years the cold and/or warm phases are damped, while in others they are amplified. When the surface ocean becomes substantially warmer than usual, we refer to it as a warm event, the most extreme of which are known as Atlantic Niños, drawing an analogy to the El Niño phenomenon in the Pacific Ocean. Conversely, when the ocean is notably cooler than usual, it is termed a cold event, the most pronounced and persistent of which are referred to as Atlantic Niñas. In short: every Atlantic Niño is a warm event, but not every warm event reaches Niño intensity. The same holds for Atlantic Niñas and cold events. For instance, the positive anomalies in the summer of 2021 met the criteria for an Atlantic Niño, whereas the positive SST anomalies observed in late 2019 were classified as a warm event.

Figure 1: Sea surface temperature (left panel) and sea surface temperature anomalies (right panel) along the equator from January 2019 (top) to September 2025 (bottom), based on measurements from temperature sensors on moored PIRATA buoys at 35°W, 23°W, 10°W, 3°W, and 0°. Under typical conditions, the equatorial Atlantic warms during boreal spring and cools during summer. However, the strength of this seasonal cycle varies from year to year (left panel). Periods with unusually strong departures from the normal cycle (right panel) appear as warm events (2019, 2021, 2024) or cold events (2024, 2025), with the most extreme of these developing into Atlantic Niños or Atlantic Niñas, respectively.

So far, scientists have discovered a hand full of recipes for Atlantic Niños and Niñas. These include interactions between the atmosphere and the upper ocean, atmospheric heat fluxes, transport of unusually cold or warm waters to the equator, variability of deep ocean currents, and interactions between the Atlantic and the Pacific (Lübbecke et al., 2018). Most of these mechanisms occur primarily during the boreal summer months (June-August), when SSTs reach their annual minimum and the vertical ocean structure is most sensitive to air-sea interactions.

In recent years, the observations (Fig. 1) reveal another warm event in early 2024, when equatorial Atlantic SSTs exceeded 30°C for the first time in 30-40 years since observations have become available. This extreme warm event was followed by a moderate cold event in summer 2024 and an extreme cold event during the summer of 2025, at the end of the record. Before confirming whether this most recent event qualifies as an Atlantic Niña, we will first revisit why these extreme events in the equatorial Atlantic matter and why continued observations are essential.

______________________________________________________________________________

Extreme events in the equatorial Atlantic impact millions of people

Extreme sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Atlantic have far-reaching impacts on regional and global climate. They influence rainfall over the surrounding continents, tropical cyclone activity, ocean currents and wave dynamics, and even carbon export from the surface layer to the deep ocean.

The location of the tropical rainfall belt, known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), is strongly tied to where the ocean is warmest. When the equatorial Atlantic is unusually warm, the ITCZ tends to shift toward the equator, leading to reduced rainfall over West Africa, but increased rainfall over Northeastern Brazil and the Gulf of Guinea (Nobre & Shukla, 1996; Rodriguez-Fonseca et al., 2015). Conversely, when the equatorial Atlantic is anomalously cold, the pattern reverses. These shifts can trigger severe droughts or floods, posing significant risks to lives, infrastructure, and agriculture.

Recent research also suggests that extreme SST anomalies in the equatorial Atlantic can affect tropical cyclone activity in the eastern Atlantic (Kim et al., 2023). Atlantic Niño conditions, in particular, may enhance cyclone development near the Cape Verde region, which is an area where many hurricanes that eventually strike the Caribbean or the U.S. originate.

In addition, extreme sea surface temperature anomalies in the equatorial Atlantic strongly influence local ocean dynamics. They can alter the speed of ocean currents, which in turn affect wave activity and the development of instabilities and mixing along the equator (Tuchen et al., 2024). These temperature anomalies also play a crucial role in regulating the ocean’s biological carbon pump. For instance, during the strong Atlantic Niño of 2021, reduced equatorial upwelling led to lower biological productivity and, consequently, reduced carbon export from the surface to the deep ocean during the boreal summer (Habib et al., 2024).

Understanding and monitoring these extreme SST events is therefore essential, not only for anticipating local climate impacts, but also for assessing their broader, indirect influence on the global climate system. For these reasons, it is essential to sustain the tropical Atlantic observing system, in particular, the PIRATA moored buoy network. Improved representation of these processes in weather and climate models is essential for developing more accurate and timely forecasts of extreme events. Yet, compared to the Pacific Ocean, where El Niño prediction skill is substantially higher, progress in the Atlantic has been slow and for many years the prediction skill for Atlantic Niño/Niña events did not advance. Recent advances in machine learning, however, offer renewed optimism, potentially enhancing the prediction of Atlantic Niño and Niña events significantly (Bachèlery et al., 2025).

______________________________________________________________________________

What is going on lately?

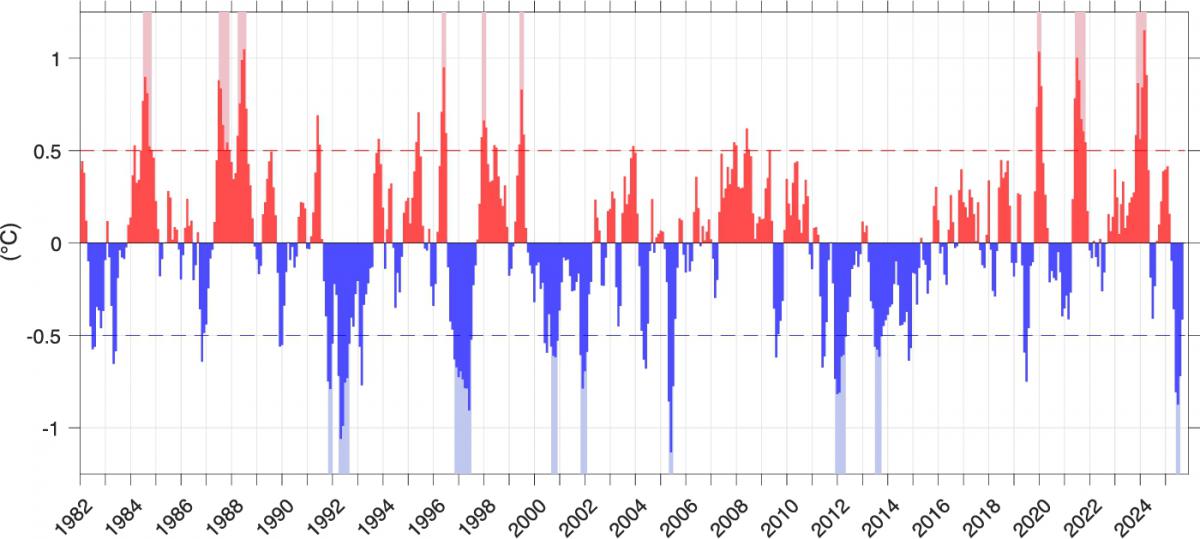

As noted at the start of this blog, the equatorial Atlantic experienced an extended period of relative calm between 2000 and 2019, with no significant warm events recorded (Fig. 2). The updated time series now clearly shows that such events have returned in recent years, highlighted by the warm anomalies of late 2019, summer 2021, and early 2024.

Figure 2: Monthly sea surface temperature anomalies in the eastern equatorial Atlantic (20°W-0°, 3°S-3°N; ATL3 region) from January 1982 to September 2025 from satellite observations. Blue bars indicate cold anomalies, red bars warm anomalies. Each value represents a mean of 3 consecutive months. Only if three consecutive mean values exceed the +- 0.5°C threshold (red and blue dashed lines) it is called warm or cold event. Such warm and cold events are marked by red and blue shadings, respectively. The long-term warming trend of 0.75°C between 1982 to 2025 has been removed from the time series.

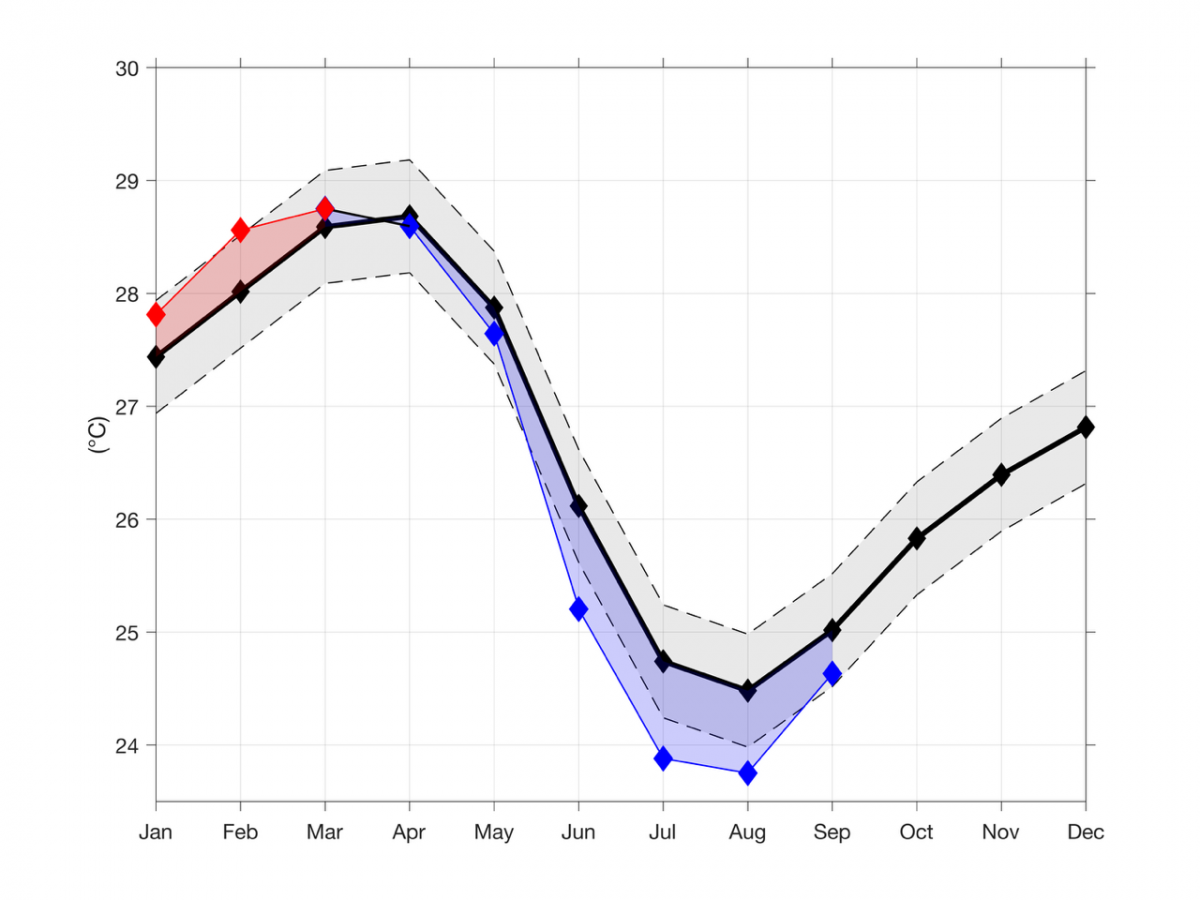

In addition, the data also reveal a marked cold anomaly during the boreal summer of 2025. Even though sea surface temperatures in early 2025 were actually above average, cold anomalies began to develop in April (Fig. 3). For three consecutive months, from June through August, the equatorial Atlantic Ocean was more than 0.5°C colder than normal which means that this event meets the criteria for an Atlantic Niña. This is the first confirmed cold event since 2013 and, with an average cold anomaly of -0.83°C between June and August, the strongest Atlantic Niña since 1992.

Figure 3: Sea surface temperature in the eastern equatorial Atlantic (20°W-0°, 3°S-3°N). The black line and dots show the typical evolution of SST. The dashed line and the grey shading indicate ±0.5°C from the normal situation. The colored line and dots show SST in 2025 so far. Red colors indicate temperatures above normal, blue colors indicate temperatures below normal. June, July, and August were more than 0.5°C colder than normal.

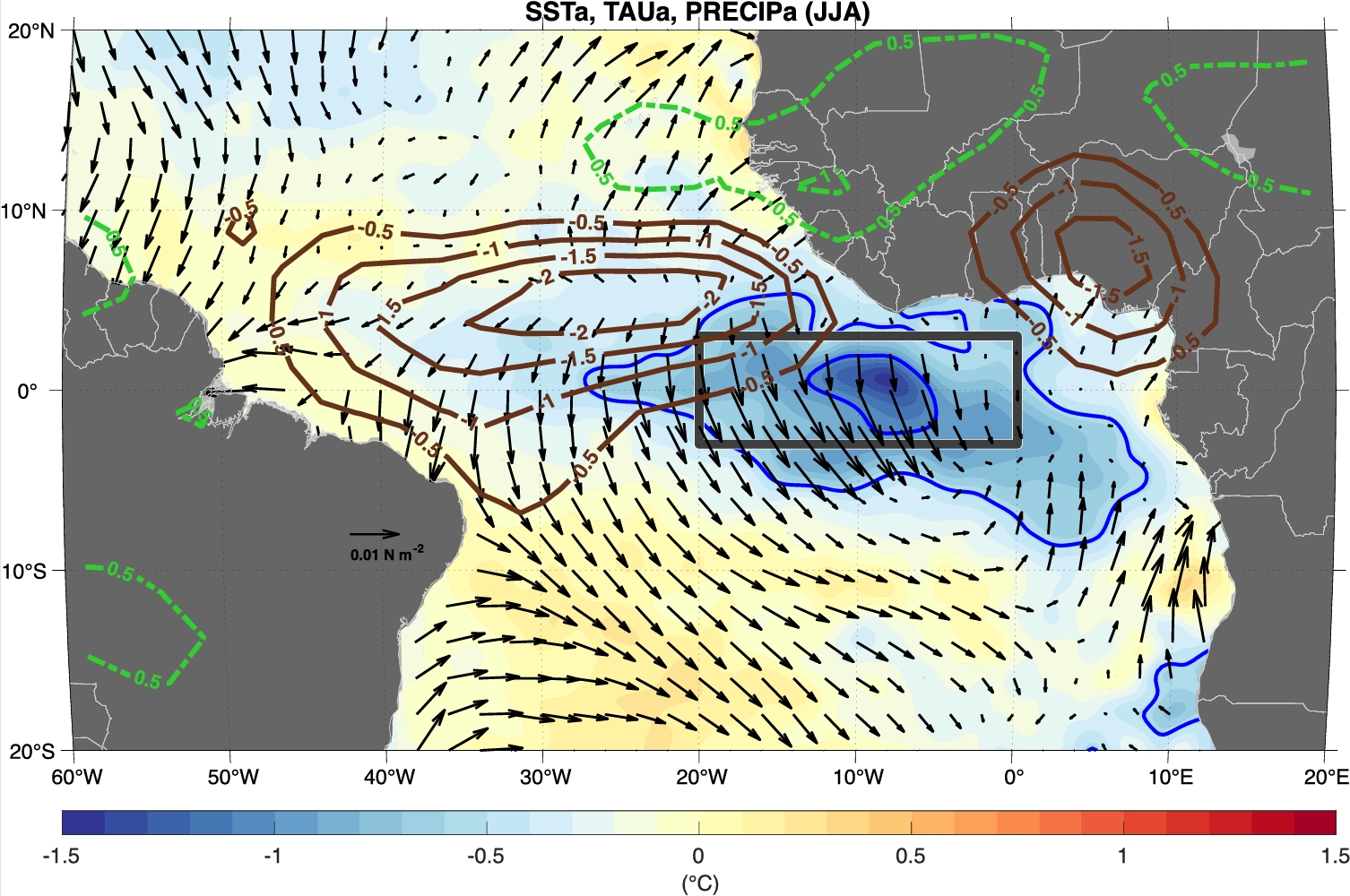

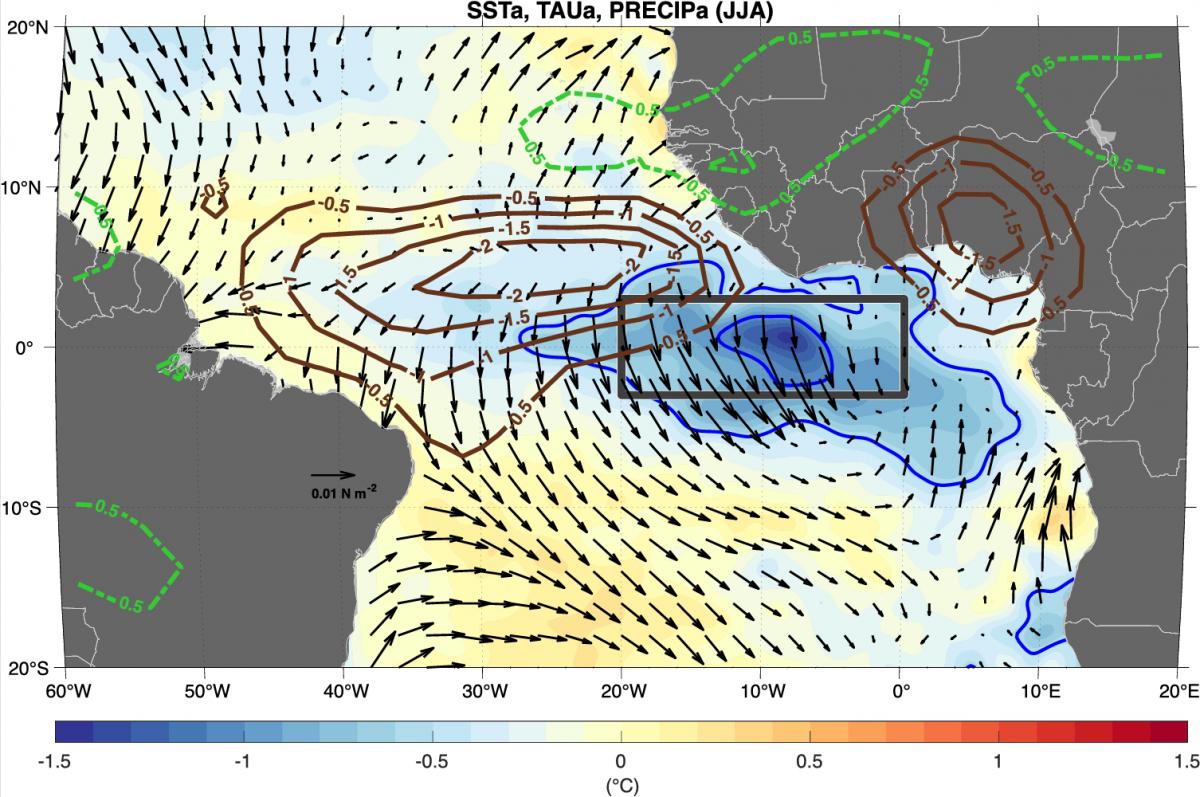

Cold SST anomalies during the summer of 2025 were clearly concentrated in the equatorial Atlantic particularly within the ATL3 region (20°W-0°, 3°S-3°N; black rectangle in Fig. 4). We further observe a weakening of the ITCZ, resulting in reduced rainfall over the Atlantic Ocean between the equator and 10°N, as well as in the Gulf of Guinea. Increased rainfall over West Africa and the Sahel region could be a sign of a slight northward shift of the ITCZ over the African continent.

Interestingly, the winds show a weakening of their typical southeasterly direction during this period. Normally, a stronger east-west temperature gradient during a cold event would enhance these winds. However, in this case, the opposite occurred which suggests that the communication between the winds and the ocean is somehow interrupted. Something that, by the way, also occurred during the summer of 2024.

Figure 4: Sea surface temperature anomalies in the tropical Atlantic (color shadings), rainfall anomalies (brown and green contour lines; in mm day-1), and wind anomalies (arrows) during June-August 2025. Most of the tropical Atlantic has been colder than normal, but the equatorial Atlantic has been extremely cold with anomalies reaching more than -1.0°C. Reduced rainfall is observed over the northern tropical Atlantic and over the Gulf of Guinea. Enhanced rainfall was observed over West Africa and Sahara. Wind anomalies also indicate a northward shift of the ITCZ.

______________________________________________________________________________

Open questions

While the occurrence of an Atlantic Niña in the summer of 2025 is confirmed, scientific understanding of this event remains in its infancy. Scientists are only beginning to investigate its onset, evolution and decay. Preliminary analyses of potential generation mechanisms have not identified a clear key driver for the 2025 Atlantic Niña, and several hypotheses remain under evaluation.

The aim of this blog is to provide a timely summary of this year’s event and highlight recent developments in the equatorial Atlantic. The 2025 Atlantic Niña was unusual in several respects. Here are some questions that keep experts awake at night:

- What were the exact mechanisms that triggered the 2025 Atlantic Niña?

- Why did the winds appear to respond to, rather than drive or sustain, the event?

- What factors explain the apparent return to high variability in the equatorial Atlantic after two decades of relative calm?

- Why have we seen more extreme events since 2019 during atypical times of the year (outside of boreal summer)?

- Why was tropical instability wave activity (not shown here, but observed at PIRATA moorings) substantially weaker than expected, despite typically being enhanced under cold conditions (Perez et al., 2012)?

Addressing these questions requires sustained, comprehensive observations. Maintaining and strengthening the tropical Atlantic observing system is therefore critical, not only to monitor and understand these events, but also to improve our ability to predict extreme sea surface temperature events in the equatorial Atlantic.

It is safe to say that high variability has returned to the equatorial Atlantic variability, but many questions remain unanswered as of now.

______________________________________________________________________________

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Joana González, Joke Lübbecke, Ingo Richter, Regina Rodrigues, and Agus Santoso for providing insightful comments and helpful suggestions.

References

Bachèlery, M.-L., Brajard, J., Patacchiola, M., Illig, S., & Keenlyside, N. (2025). Predicting Atlantic and Benguela Niño events with deep learning. Science Advances, 11(14), eads5185, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ads5185

Habib, J., Stemmann, L., Accardo, A., Baudena, A., Tuchen, F. P., Brandt, P., & Kiko, R. (2024). Marine snow surface production and bathypelagic export at the equatorial Atlantic from an imaging float. EGUsphere, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-3365

Kim, D., Lee, S.-K., Lopez, H., Foltz, G. R., Wen, C., & Dunion, J. (2023). Increase in Cape Verde hurricanes during Atlantic Niño. Nature Communications, 14(1), 3704, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39467-5

Lee, S.-K., Lopez, H., Tuchen, F. P., Kim, D., Foltz, G. R., & Wittenberg, A. T. (2023). On the Genesis of the 2021 Atlantic Niño. Geophysical Research Letters, 50(16), e2023GL104452, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL104452

Lübbecke, J. F., Rodríguez-Fonseca, B., Richter, I., Martín-Rey, M., Losada, T., Polo, I., & Keenlyside, N. (2018). Equatorial Atlantic variability – Modes, mechanisms, and global teleconnections. WIREs Climate Change, 9(4), e527, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.527

Nobre, P., & Shukla, J. (1996). Variations of Sea Surface Temperature, Wind Stress, and Rainfall over the Tropical Atlantic and South America. Journal of Climate, 9(10), 2464-2479, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1996)009<2464:VOSSTW>2.0.CO;2

Perez, R. C., Lumpkin, R., Johns, W. E., Foltz, G. R., & Hormann, V. (2012). Interannual variations of Atlantic tropical instability waves. Journal of Geophysical Research, 117, C03011, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007584

Prigent, A., Lübbecke, J. F., Bayr, T., Latif, M., & Wengel, C. (2020). Weakened SST variability in the tropical Atlantic Ocean since 2000. Climate Dynamics, 54(5-6), 2731-2744, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-020-05138-0

Richter, I., Tokinaga, H., & Okumura, Y. M. (2022). The Extraordinary Equatorial Atlantic Warming in Late 2019. Geophysical Research Letters, 49(4), e2021GL095918, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL095918

Rodriguez-Fonseca, B. (2015). Variability and Predictability of West African Droughts: A Review on the Role of Sea Surface Temperature Anomalies. Journal of Climate, 28(10), 4034-4060, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00130.1

Tuchen, F. P., Perez, R. C., Foltz, G. R., Brandt, P., Subramaniam, A., Lee, S.-K., Lumpkin, R., & Hummels, R. (2024). Modulation of Equatorial Currents and Tropical Instability Waves During the 2021 Atlantic Niño. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 129(1), e2023JC020431, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JC020431

Tuchen, F. P., Foltz, G. R., Lee, S.-K., Perez, R. C., Prigent, A., Brandt, P., McPhaden, M. J., Lopez, H., Kim, D., & West, R. (2025). Record Warmth and Unprecedented Drop in Equatorial Atlantic Sea Surface Temperatures in 2024. Geophysical Research Letters, 52(12), e2025GL115973, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GL115973